Loggerhead turtle. Credit: M. Godfrey, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Loggerhead turtle. Credit: M. Godfrey, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Loggerhead turtle. Credit: M. Godfrey, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

About the Species

Loggerhead turtle. Credit: M. Godfrey, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Loggerhead turtle. Credit: M. Godfrey, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Loggerhead turtle. Credit: M. Godfrey, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

The loggerhead turtle is named for its large head, which supports powerful jaw muscles that enable them to feed on hard-shelled prey, such as whelks and conch. Loggerheads are the most abundant species of sea turtle that nests in the United States. Juvenile and adult loggerheads live in U.S. coastal waters, but many adults that nest on U.S. beaches migrate from neighboring nations like the Bahamas, Cuba, and Mexico.

Loggerhead populations in the United States declined due to bycatch in fishing gear such as trawls, gillnets, and longlines. The use of turtle excluder devices (TEDs) in shrimp trawls, gillnet bans, and other gear modification have reduced sea turtle bycatch in some fisheries, but bycatch in fishing gear remains the biggest threat facing loggerheads.

NOAA Fisheries and our partners are dedicated to protecting and recovering sea turtle populations worldwide. We use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and recover these threatened and endangered species. We engage our partners as we develop measures and recovery plans that foster the conservation and recovery of loggerhead turtles and their habitats.

Population Status

Loggerhead turtles are found worldwide with nine distinct population segments (DPS) listed under the Endangered Species Act. The most recent reviews show that only two loggerhead nesting beaches have greater than 10,000 females nesting per year: South Florida and Oman. Oman hosts the second largest nesting assemblage of loggerheads in the world, but recent trends analyses indicate this important nesting population is declining.

In the United States, the Northwest Atlantic Ocean DPS of loggerhead turtles nests primarily along the Atlantic coast of Florida, South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina and along the Florida and Alabama coasts in the Gulf of Mexico. Total estimated nesting in the United States is more than 100,000 nests per year.

Loggerheads nest sparsely throughout the Caribbean, on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean (Cape Verde Islands and Brazil), in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, throughout the Indian Ocean in small numbers (with the exception of Oman), and in the North and South Pacific Ocean.

In the Pacific, there are two distinct population segments of loggerheads. The North Pacific Ocean DPS nests only on the coasts of Japan. This population has declined 50 to 90 percent during the last 60 years, however the overall nesting trend in Japan has been stable or slightly increasing over the last decade. The South Pacific Ocean DPS nests primarily in Australia with some nesting in New Caledonia. In 1977, about 3,500 females may have nested in the South Pacific—today there are only around 500 per year.

The 2009 status review of the loggerhead sea turtle and the 5-Year Review of the North Pacific Ocean Distinct Population Segment of Loggerhead Sea Turtle provide additional population information for this species.

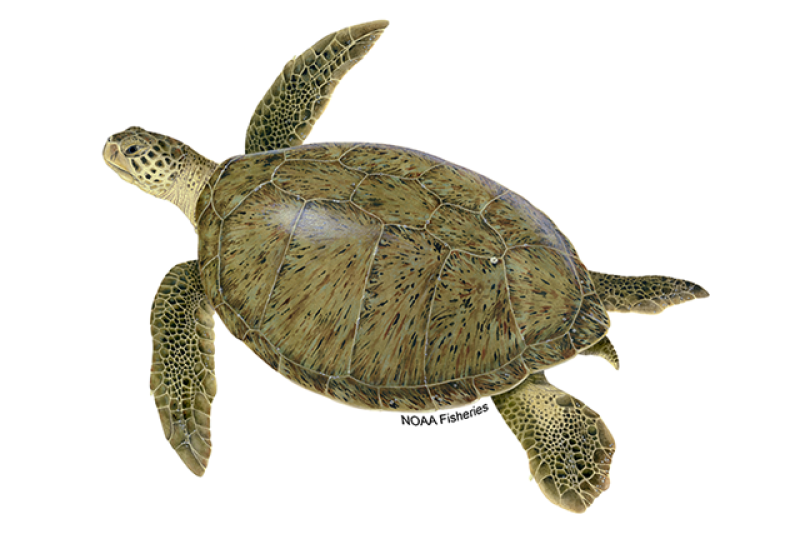

Appearance

Loggerhead turtles have large heads with powerful jaws. The top shell (carapace) is slightly heart-shaped and reddish-brown in adults and sub-adults, while the bottom shell (plastron) is generally a pale yellowish color. The neck and flippers are usually dull brown to reddish brown on top and medium to pale yellow on the sides and bottom. Unlike freshwater turtles and tortoises, sea turtles cannot withdraw their head or flippers into their shells. Hatchlings are mostly dark brown, their flippers have white to white-gray margins, and the bottom shell is generally yellowish to tan.

Behavior and Diet

Loggerhead turtles, like all sea turtles, are marine reptiles and must come to the surface to breathe air. Adult female sea turtles return to land to lay their eggs in the sand—they are remarkable navigators and usually return to a beach in the general area where they hatched decades earlier.

The life history of loggerhead turtles involves a series of stages of development from hatchling to adult. Hatchlings and juveniles spend the first 7 to 15 years of their lives in the open ocean. Then they migrate to nearshore coastal areas where they will forage and continue to grow for several more years. Adult loggerhead turtles migrate hundreds to thousands of kilometers from their foraging grounds to their nesting beaches.

Through satellite tracking, researchers have discovered that loggerheads in the Pacific undertake a trans-Pacific migration. Hatchlings from nesting beaches in Japan and Australia migrate across the Pacific to feed off the coast of Baja California, Mexico, Peru and Chile—nearly 8,000 miles! They spend many years (possibly up to 20 years) growing to maturity and then migrate back to the beaches where they hatched in the Western Pacific Ocean to mate and nest and live out the remainder of their lives.

Loggerheads are carnivores, only occasionally consuming plant material. During their open ocean phase, they feed on a wide variety of floating items. Unfortunately, trash and other debris discarded by humans also tends to accumulate in their habitat. Small fragments of plastic are often mistaken for food and eaten by turtles. Juveniles and adults in coastal waters eat mostly bottom dwelling invertebrates such as whelks, other mollusks, horseshoe crabs, and other crabs. Their powerful jaws are designed to crush their prey.

Where They Live

Loggerhead turtles are found worldwide primarily in subtropical and temperate regions of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, and in the Mediterranean Sea. In the Atlantic, the loggerhead turtle's range extends from Newfoundland to Argentina. In the eastern Pacific, loggerheads have been reported from Alaska to Chile.

World map providing approximate representation of the loggerhead turtle's range.

World map providing approximate representation of the loggerhead turtle's range.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Loggerhead sea turtles are long-lived and could live 70 to 80 years or more. Female loggerheads reach maturity at about 35 years of age. Every 2 to 3 years they mate in coastal waters and return to nest on a beach in the general area where they hatched decades earlier.

In the northern hemisphere, mating occurs in late March to early June and females lay eggs between late April and early September. Loggerheads are solitary, night-time nesters, and they generally prefer high energy, relatively narrow, steeply sloped, coarse-grained beaches for nesting. Adult females lay three to five nests, sometimes more, two weeks apart during a single nesting season. Each nest contains about 100 eggs. The sex of hatchlings is determined by the temperature of the sand—cooler temperatures produce males and warmer temperatures produce females. After about 2 months incubating in the warm sand, the eggs hatch and the hatchlings make their way to the water. Newly hatched loggerhead turtles are susceptible to predators. They are particularly threatened by artificial beachfront lighting, which can disorient them and prevent them from finding the sea. Hatchlings orient by moving away from the darkest silhouette of the landward dune or vegetation to crawl towards the brightest horizon. On undeveloped beaches, this is toward the open horizon over the ocean. However, in areas with artificial lighting hatchlings are disoriented and often crawl landward instead of toward the ocean. Artificial light can similarly disorient nesting female turtles.

Threats

Bycatch in Fishing Gear

A primary threat to sea turtles is their unintended capture in fishing gear which can result in drowning or cause injuries that lead to death or debilitation (for example, swallowing hooks). The term for this unintended capture is bycatch. Sea turtle bycatch is a worldwide problem. The greatest continuing primary threat to loggerhead turtle populations worldwide is bycatch in fishing gear, primarily in trawls, longlines, gillnets, hook and line, but also in pound nets, pot/traps, and dredge fisheries.

Loss and Degradation of Nesting Habitat

Coastal development and rising seas from climate change are leading to the loss of critical nesting beach habitat for loggerhead turtles. Shoreline hardening or armoring (e.g., seawalls) can result in the complete loss of dry sand suitable for successful nesting. Artificial lighting on and near nesting beaches can deter nesting females from coming ashore to nest and can disorient hatchlings trying to find the sea after emerging from their nests.

Vessel Strikes

Vessel strikes are a major threat to loggerhead turtles near developed coastlines throughout their range. Various types of watercraft can strike loggerhead turtles when they are at or near the surface resulting in injury or death. In the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, the number of loggerhead turtle deaths due to vessel strikes are increasing. High traffic boat areas such as marinas and inlets present a higher risk. Adult loggerhead turtles, in particular nesting females, are more susceptible to vessel strikes when making reproductive migrations and while they are nearshore during the nesting season.

Direct Harvest of Turtles and Eggs

Historically, sea turtles including loggerheads were killed for their meat and their eggs which are collected for consumption in some countries. Presently, loggerhead turtles are protected in many countries where they occur, but in some places, the killing of loggerheads and collection of eggs continue to be a threat.

Ocean Pollution/Marine Debris

Increasing pollution of nearshore and offshore marine habitats threatens all sea turtles. Loggerhead turtles may die after ingesting fishing line, plastic bags and other plastic debris, floating tar or oil, and other materials discarded by humans which they can mistake for food. They can also become entangled in marine debris, including lost or discarded fishing gear, and can be killed or seriously injured.

Climate Change

For all sea turtles, a warming climate is likely to result in changes in beach morphology and higher sand temperatures which can be lethal to eggs, or alter the ratio of male and female hatchlings produced. Rising seas and storm events cause beach erosion which may flood nests or wash them away. Changes in the temperature of the marine environment are likely to alter the abundance and distribution of food resources, leading to a shift in the migratory and foraging range and nesting season of loggerheads.

Scientific Classification

| Animalia |

Chordata |

Reptilia |

Testudines |

Cheloniidae |

Caretta |

caretta |

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/21/2024