Some things just get better with age. Like rockfish mothers.

A rockfish might not start spawning until she is 25 years old. As she gets older she produces more, and more robust, young. She continues to produce them over many years, into advanced age – which for some rockfish means 100 or 200 years.

That is the sluggish end of the spectrum, but rockfish in general are slow-growing, late-maturing, long-lived species. This evolutionary strategy has helped rockfish weather difficult times over millennia—but makes them highly vulnerable to overfishing. Recovering from fishing pressure is another thing rockfish do slowly.

To set sustainable fishing quotas for any fishery, managers need to know how many fish there are now, and how many to expect in the future. Understanding the reproductive biology of a species—when females produce young, how many, and how often—is essential to predicting future production.

With rockfish, it’s complicated.

Rockfish species have developed complex reproductive strategies to increase the likelihood of survival for their young. They are livebearers, protecting their young during the earliest stages of development. Late maturity and increased productivity with age may ensure that females are large enough to have energy reserves to sustain production during difficult times. A long reproductive lifespan increases the chance that some young will be born during good years. Some species skip spawning in some years, possibly saving their efforts for years with better conditions for embryo development, or channeling energy into their own growth and survival to increase future reproductive success.

To further complicate things, reproductive biology changes from species to seemingly similar species, and can vary with location and environmental conditions.

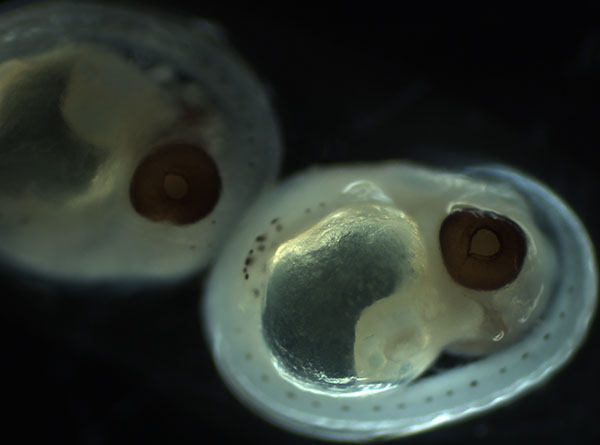

Rockfish embryos - Photo: Christina Conrath, NOAA Fisheries

NOAA Fisheries scientist Christina Conrath of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center set out to collect maturity and reproductive data to improve stock assessments for three deepwater rockfish species. Until now, little was known about the reproductive biology of rougheye, blackspotted, and shortraker rockfish. Conrath got new maturity data, and some surprises.

“The most exciting part of this research was documenting skip spawning for the first time for these species,” said Conrath “High rates in all three species—from 37% in rougheye to 94% in blackspotted–suggest that this is an important reproductive strategy. It opens a lot of questions for further research: is skip spawning constant, or related to environmental conditions, or to female condition or age or size?”

Another important finding was a marked difference in the age that rougheye and blackspotted rockfish reach reproductive maturity. Until recently, these were thought to be one species, and are still managed as one complex. Conrath found the age at maturity for rougheye was less than 20 years; for blackspotted, over 27 years. That age difference has important implications for managing these species.

“These numbers directly influence stock assessments of how many mature females there are,” Conrath explains. “Because of the effect on spawning stock size, a small change in age at maturity can have a big impact on how many fish can be caught.”

These new findings provide managers with information they need to ensure that deepwater Alaska rockfish populations stay healthy. They also advance our knowledge of the various ways rockfish can adjust their reproduction, and that raises new questions.

“An ongoing challenge in rockfish research will be to determine which mechanisms rockfish are most likely to use in different environmental conditions,” says Conrath. ”How much they can adapt their reproductive strategies to a changing climate?”