Staghorn Coral

Acropora cervicornis

Protected Status

Quick Facts

Acropora cervicornis staghorn coral. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Acropora cervicornis staghorn coral. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Acropora cervicornis staghorn coral. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

About the Species

Acropora cervicornis staghorn coral. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Acropora cervicornis staghorn coral. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Acropora cervicornis staghorn coral. Credit: NOAA Fisheries

Staghorn coral is one of the most important corals in the Caribbean. It, along with elkhorn coral and star corals (boulder, lobed, and mountainous) built Caribbean coral reefs over the last 5,000 years. Staghorn coral can form dense groups called “thickets” in very shallow water. These provide important habitat for other reef animals, especially fish.

In the early 1980s, a severe disease event caused major mortality throughout its range and now the population is less than 3 percent of its former abundance. The greatest threat to staghorn coral is ocean warming, which causes the corals to release the algae that live in their tissue and provide them food, usually causing death. Other threats to staghorn coral are ocean acidification (decrease in water pH caused by increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere) that makes it harder for them to build their skeleton, unsustainable fishing practices that deplete the herbivores (animals that feed on plants) that keep the reef clean, and land-based sources of pollution that impacts the clear, low nutrient waters in which they thrive.

NOAA Fisheries and our partners are dedicated to conserving and recovering the staghorn coral populations throughout its range. We use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and restore these threatened corals. We engage our partners as we develop regulations and management plans that foster healthy coral reefs and reduce the impacts of climate change, unsustainable fishing, and land-based sources of pollution.

Population Status

Staghorn coral used to be a dominant coral on Caribbean reefs and was so abundant that an entire reef zone is named for it. Beginning in the 1980s, the staghorn coral population declined 97 percent from white band disease. This disease kills the coral’s tissues. Populations appear to consist mostly of isolated colonies or small groups of colonies compared to the vast thickets once prominent throughout its range, with thickets still a prominent feature at only a handful of known locations. Successful reproduction is very rare, so it is hard for staghorn coral populations to increase.

Appearance

Staghorn coral colonies are golden tan or pale brown with white tips and they get their color from the algae that live within their tissue. Staghorn corals have antler-like branches and typically stem out from a central trunk and angle upward. Branches are typically 1–3 inches thick. Individual colonies can grow to at least 4 feet in height and 6 feet in diameter. Staghorn coral colonies can grow in dense stands and form an interlocking framework known as thickets. Each staghorn coral colony is made up of many individual polyps that grow together. Each polyp is an exact copy of all the polyps in the same colony.

Behavior and Diet

Staghorn coral get food from photosynthetic algae that live inside the coral's cells. They also feed by capturing plankton with their polyps’ tentacles. Coral bleaching is the loss of the algae that live in coral tissue. This loss can lead to coral death through starvation or increased vulnerability to diseases.

Due to their bush-like growth form, staghorn corals provide complex habitat for fish and other coral reef organisms. When staghorn corals are abundant, they provide shoreline protections from large waves and storms.

Where They Live

Staghorn coral is found typically in clear, shallow water (15–60 feet) on coral reefs throughout the Bahamas, Florida, and the Caribbean. The northern extent of the range in the Atlantic Ocean is Palm Beach County, Florida, where it is relatively rare. Staghorn coral lives in many coral reef habitats including spur and groove, bank reef, patch reef, and transitional reef habitats, as well as on limestone ridges, terraces, and hardbottom habitats. NOAA Fisheries has designated four critical areas determined to provide critical recruitment habitat for staghorn corals off the coast of Florida and off the islands of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

World map providing approximate representation of the Staghorn coral's range

World map providing approximate representation of the Staghorn coral's range

Lifespan & Reproduction

Staghorn coral reaches reproductive maturity at about 7 inches tall. Staghorn coral is a simultaneous hermaphrodite, meaning each colony produces both eggs and sperm, but usually does not self-fertilize. Staghorn coral sexually reproduces once per year after the full moon in late summer by “broadcast spawning” eggs and sperm into the water column. Fertilized eggs develop into larvae that settle on hard surfaces and form new colonies. Staghorn coral can also form new colonies when broken pieces, called fragments, re-attach to hard surfaces. Staghorn coral is one of the fastest growing corals—when healthy, it can grow up to 8 inches in branch length per year.

Threats

Climate Change

Climate change is the greatest global threat to corals. Scientific evidence now clearly indicates that the Earth's atmosphere and oceans are warming, and that these changes are primarily due to greenhouse gases derived from human activities. As temperatures rise, mass coral bleaching events and infectious disease outbreaks are becoming more frequent. Additionally, carbon dioxide absorbed into the ocean from the atmosphere has already begun to reduce calcification rates in reef-building and reef-associated organisms by altering seawater chemistry through decreases in pH. This process is called ocean acidification.

Diseases

Diseases can cause adult mortality, reducing sexual and asexual reproductive success, and impairing colony growth. Coral diseases are caused by a complex interplay of factors including the cause or agent (e.g., pathogen, environmental toxicant), the host, and the environment. Coral disease often produces acute tissue loss. Staghorn coral is particularly susceptible to white band and white plague diseases.

Unsustainable Fishing Pressure

Fishing, particularly unsustainable fishing, can have large-scale, long-term ecosystem-level effects that can change ecosystem structure from coral-dominated reefs to algal-dominated reefs (“phase shifts”). This results from the removal of fish that eat algae and keep the reef clean to allow for space for corals to grow.

Land-Based Sources of Pollution

Impacts from land-based sources of pollution—including coastal development, deforestation (clearing a wide area of trees), agricultural runoff, and oil and chemical spills—can impede coral growth and reproduction, disrupt overall ecological function, and cause disease and mortality in sensitive species. It is now well accepted that many serious coral reef ecosystem stressors originate from land-based sources, most notably toxicants, sediments, and nutrients.

Scientific Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum | Cnidaria |

| Class | Anthozoa |

| Order | Scleractinia |

| Family | Acroporidae |

| Genus | Acropora |

| Species | cervicornis |

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/21/2024

What We Do

Conservation & Management

We are committed to the protection and recovery of staghorn coral through implementation of various conservation, regulatory, and restoration measures. Our work includes:

- Protecting habitat and designating critical habitat

- Breeding staghorn corals in nurseries and planting them into the wild

- Increasing staghorn coral resilience to climate change

- Rescuing injured staghorn corals after ship groundings or major storm events

Science

We conduct various research activities on the biology, behavior, and ecology of staghorn coral. The results of this research are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this threatened species. Our work includes:

- Tracking individuals over time to understand population trends and causes of death

- Conducting spawning observations and collection of eggs and sperm for culturing staghorn coral larvae

- Conducting temperature and acidification experiments on eggs, sperm, larvae, and newly settled colonies

- Conducting experiments to enhance the success of staghorn coral propagation efforts

How You Can Help

Conserve Energy

Use energy efficient lighting, bike to work, or practice other energy-saving actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Climate change is one of the leading threats to coral reefs.

Conserve Water

The less water you use, the less runoff and wastewater carrying nutrients, sediments, and toxins into the ocean.

Practice Safe Boating

Anchor in sandy areas away from coral and obey aids-to-navigation/signage to make sure you do not accidentally injure corals that are just below the surface.

Reduce Chemical/Sunscreen Pollution

Choose sunscreen with zinc oxide or titanium dioxide over those containing oxybenzone, which is toxic to corals.

Featured News

Shallow water provides habitat for branching corals (Acropora spp), as seen here on a reef flat in Guam. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Jonathan Brown

Shallow water provides habitat for branching corals (Acropora spp), as seen here on a reef flat in Guam. Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Jonathan Brown

The branches of fast-growing elkhorn coral provide important habitat for fish. Populations of this iconic coral have declined across the Caribbean due to disease, bleaching and storms. Credit: NOAA

The branches of fast-growing elkhorn coral provide important habitat for fish. Populations of this iconic coral have declined across the Caribbean due to disease, bleaching and storms. Credit: NOAA

Restored staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) at Looe Key reef in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Staghorn coral, along with elkhorn coral and star corals, built Caribbean coral reefs over the last 5,000 years. NOAA Fisheries and partners are using a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and restore these threatened corals. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Restored staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) at Looe Key reef in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Staghorn coral, along with elkhorn coral and star corals, built Caribbean coral reefs over the last 5,000 years. NOAA Fisheries and partners are using a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and restore these threatened corals. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Management Overview

The staghorn coral is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Additionally, the staghorn coral is listed under:

- Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

- Annex II of the Protocol for Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW)

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Recovery Action

Under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries is required to develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of listed species. The ultimate goal of the staghorn coral recovery plan is to recover the species so it no longer needs the protection of the ESA. We must combat both global and local threats to help protect staghorn corals.

The major actions recommended in the plan are:

- Improve understanding of population abundance, trends, and structure through monitoring and experimental research.

- Develop and implement appropriate strategies for population enhancement through restocking and active management (PDF, 39 pages).

- Implement ecosystem-level actions to improve habitat quality and restore keystone species. The goal is to restore and protect adult colonies to promote successful natural recruitment in the long term.

- Curb ocean warming and acidification impacts to health, reproduction, and growth, and possibly curb disease threats, by reducing atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations.

- Reduce locally-manageable stress and mortality threats (e.g., predation, physical damage, sedimentation, nutrients, contaminants).

- Determine coral health risk factors and their inter-relationships and implement mitigation or control strategies to minimize or prevent impacts to coral health.

Read the recovery plan for staghorn coral

Species Recovery Contact

- Alison Moulding, Southeast Corals Recovery Coordinator

Implementation

ARIT Products

Project Implementation Table (MS Excel). This table contains an inventory of projects related to implementation of the recovery plan for staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) and elkhorn coral (A. palmata). The worksheet "Recovery Plan Actions" lists the actions from the recovery plan and their action number. The worksheet "Completed" lists all known completed projects that address actions in the recovery plan. Projects in progress are listed either in the "Long-term" worksheet for those that are ongoing or in the "ALL" worksheet for projects that will have an end-date. Please send updates and additions to Alison Moulding (alison.moulding@noaa.gov), NOAA Fisheries Southeast Regional Office.

Cryobanking Strategy (PDF, 13 pages). This document identifies a strategy and recommendations for range-wide collection of Acropora sperm for cryobanking.

Critical Habitat Designation

Once a species is listed under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries evaluates and identifies whether any areas meet the definition of critical habitat. Those areas may be designated as critical habitat through a rule making process. The designation of an area as critical habitat does not create a closed area, marine protected area, refuge, wilderness reserve, preservation, or other conservation area; nor does the designation affect land ownership. Federal agencies that undertake, fund, or permit activities that may affect these designated critical habitat areas are required to consult with NOAA Fisheries to ensure that their actions do not adversely modify or destroy designated critical habitat.

For staghorn corals, facilitating increased successful sexual and asexual reproduction is the key objective to the conservation of these species. NOAA Fisheries has designated (73 FR 72210) four critical habitat areas in Florida, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands to protect substrate for recruitment.

Conservation Efforts

Working to Enhance Populations

Severely reduced successful reproductive recruitment into the population is one of the major things impeding recovery of staghorn corals. There are many factors that are contributing to this problem. NOAA Fisheries, with many partners, are taking several steps to help, including:

- Establishing a network of coral nurseries throughout the species’ range to grow and asexually produce fragments and outplant them to the reef.

- Developing a plan to guide staghorn coral population enhancement (PDF, 39 pages) which coral restoration partners, including non-governmental organizations, academia, zoos, aquaria, and federal, state, and local agencies, are requested to follow.

- Researching and implementing sexual reproduction techniques such as cryopreservation (preserving through a cooling process) of sperm and collection and fertilization of eggs and sperm for short-term rearing in the lab and outplanting to the reef.

Responding to Physical Impacts

Ship grounding and other physical impacts can break the branching staghorn corals. If the broken fragments are stabilized quickly after being broken, the corals can survive and continue to grow. NOAA Fisheries supports a program to respond to these events in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands where tens of thousands of corals have been rescued.

Conserving Coral Reefs

NOAA Fisheries is part of the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program which brings together a team of various expertise from across NOAA to understand and conserve coral reef ecosystems. The NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program focuses on implementing projects to address the impacts from the top three recognized global threats to coral reefs: climate change (including ocean acidification), land-based sources of pollution, and unsustainable fishing practices.

Protective Regulations

NOAA Fisheries issued a protective regulation called a "4(d) rule" ;to prohibit import, export, commercial activities, and take including killing, harming, and collecting staghorn coral.

Key Actions and Documents

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/21/2024

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts various research activities on the biology, behavior, ecology, and threats to staghorn coral. The results of this research are used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this threatened species.

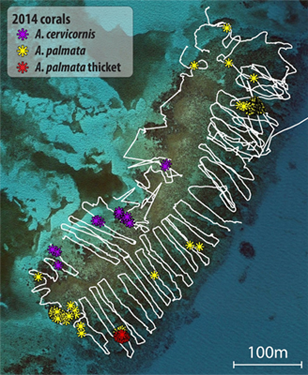

Status Assessments

Determining the size of the staghorn coral population—and whether it is increasing or decreasing from year to year—helps resource managers assess the success of the conservation measures enacted. Staghorn corals resemble tumbleweeds of the prairie in that they are often dislodged and tumble to a new place on the reef where they can re-attach and keep growing. This makes tracking individual colonies, and identifying ones that are truly new to a population, more difficult than for other coral species. Thus, monitoring the trends in staghorn coral use somewhat novel methods. For example, snorkelers can use handheld GPS units to mark all the staghorn colonies in a given shallow reef area to give a total abundance. This can be repeated over time to look for change.

Also, NOAA’s national coral reef monitoring program tallies colony size and density for all coral species in reef habitats throughout U.S. jurisdictions. This broad scale monitoring program can give useful information about status and trends for coral species that are abundant enough to be detected in this survey.

Researching Staghorn Coral Structures

It is well known that staghorn coral creates important habitat for fish by forming branchy thickets. However, current populations of staghorn coral contain fewer and possibly poorer-quality thickets than when the species was abundant. Also, it is hard to measure "how much" staghorn coral makes a functional thicket. NOAA Fisheries sought out the densest staghorn thickets that persist in different regions to quantify how much staghorn coral was in the thicket (i.e., the total length of staghorn branches per square meter of thicket area).

Structures that looked like staghorn thickets in the Dry Tortugas actually had double the density of staghorn branches as the thickets in three other regions, including southeast Florida, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. These "super-thickets" in the Dry Tortugas also housed significantly more fish and more fish species. Staghorn corals and experimental seaweed clumps that were placed in these Dry Tortugas super-thickets also had higher nutrient content than controls from nearby sparse staghorn sites. This suggests that there may be beneficial feedbacks between corals and fish when staghorn corals grow in more dense thickets than currently occur throughout most of the species range. This result also suggests that staghorn coral restoration efforts may benefit from creating even higher density stands than are currently present in many regions, and that restoring corals in areas with abundant fish, such as no-take reserves, may benefit the corals themselves.

Restoration of Threatened Corals

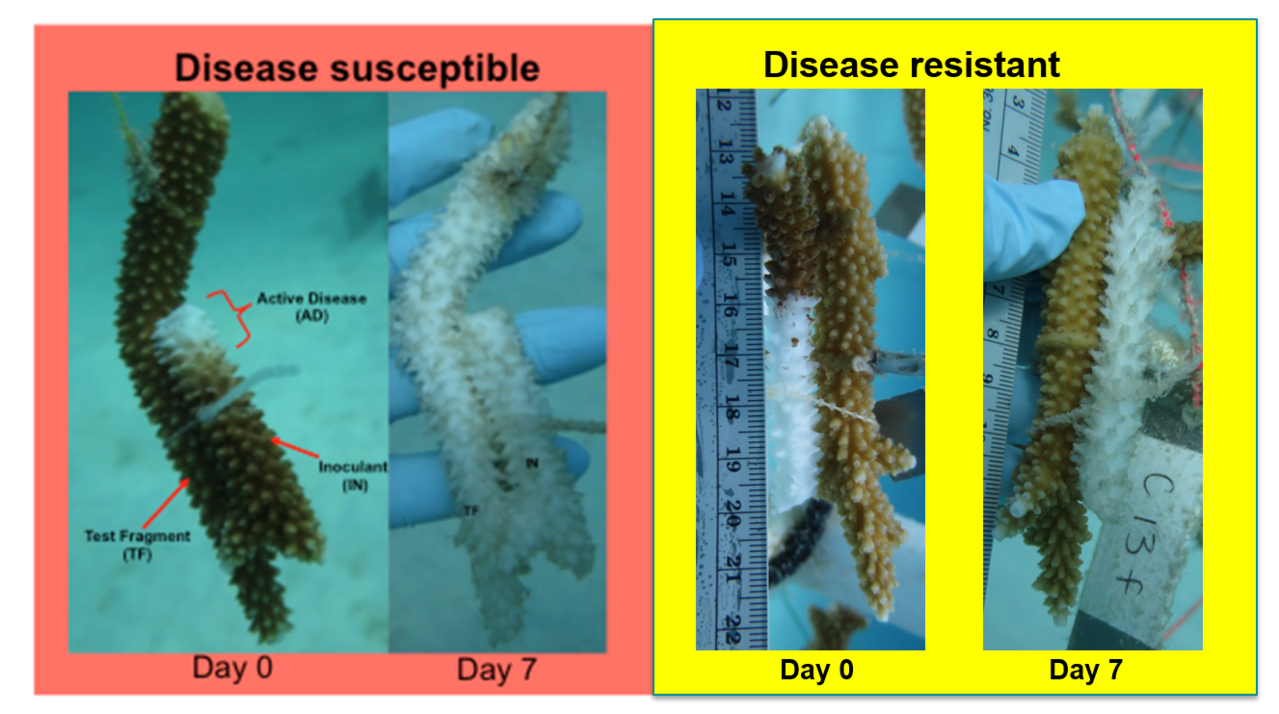

NOAA Fisheries and partners have ramped up population enhancement of staghorn corals. This developing field is supported by NOAA Fisheries’ research program to reduce uncertainties and enhance success in coral outplanting restoration activities. Disease is an important factor that impairs both the natural recovery of ESA-listed corals and the success of restored corals. Previous work compared the disease dynamics in wild versus outplanted staghorn sites and determined different health management strategies were not needed for restored populations. Several studies involve understanding coral predators and if predator removal efforts or simple mitigation actions can reduce the impact of predation on restored staghorn coral.

An ongoing study is testing coral genotypes (unique individuals) that are being cultured for restoration to determine their relative disease susceptibility or resistance. This involves exposing healthy nursery fragments to a diseased coral fragment within the nursery to determine the likelihood of transmission. A standard protocol has been developed to enable coral nurseries to screen their own populations in a comparable way. Inherent disease resistance of some coral genetic individuals may serve as an important tool both to advance our understanding of the biological mechanisms of disease resistance (and potentially effective treatments) in corals and to improve the resilience of restored coral populations.

Early Life History Studies and Restoration via Larval Corals

NOAA Fisheries coordinates spawning observations and larval culture with a network of researchers working throughout the Caribbean, including academic researchers and professional aquarists from public zoos and aquaria. Broadcast-spawning corals, like staghorn, release eggs and sperm into the water column for fertilization only over a few nights per year. NOAA Fisheries collects sperm and eggs, fertilizes them and cultures and observes the larvae in the lab to better understand factors that may enhance the likelihood of larvae successfully settling and surviving to adulthood. We also conduct experiments to understand the impacts of current and future ocean warming on these vulnerable early life stages of corals. An ongoing goal is also to develop reliable methods to culture the baby corals to adulthood in order to enhance coral recovery on the reef by adding new genetic individuals. This involves field experiments settling baby corals on different types of substrates or coatings that may enable them to survive amidst the "jungle" of encroaching competitors.

Learn more about the latest coral spawning observations from the Florida Keys (PDF, 6 pages)

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/21/2024

Documents

Caribbean Corals 5-Year Review

NOAA Fisheries has published a 5-year review of staghorn coral, elkhorn coral, pillar coral, rough…

Recovery Plan for Elkhorn Coral (Acropora palmata) and Staghorn Coral (A. cervicornis)

A recovery plan to identify a strategy for rebuilding and assuring the long-term viability of…

Proceedings of the Caribbean Acropora Workshop: Potential Application of the U.S. Endangered Species Act as a Conservation Strategy, Miami, Florida

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-24 Workshop Date: April 16-18, 2002

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 11/21/2024